This

work is directed to architects and to everyone who is interested in

the great events of architectural creativity. Its topic is the Curutchet

House, an exemplary work designed by Le Corbusier in the city of La

Plata in faraway Argentina, distant from the main centers of architectural

production and eclipsed by the large volume of LC's work. During the

time in which the Curutchet house was designed and built (1949-1955),

LC was developing some of the most important projects of his career,

which would confirm his place in the history of architecture and urban

planning. Christian Norberg Schulz wrote in 1974 that in general, all

of LC's later period can be considered the most important actualization

of architecture in the twentieth century (1). According to this view,

the works that belong to the same period as the Curutchet house may

constitute a prelude to the above period. These works (2) include the

following: St. Dié (1946-1951); L' Unité Habitation, Marseilles (1946-1952);

Roq et Rob, Cap Martin (1949); Chandigarh Capitol Buildings, India:

Secretariat (1951-1957), High Court Building (1951-1956); Les Maisons

Jaoul, Neuilly (1952-1955); Notre Dame du Haut, Ronchamp (1950-1955),

and others. The above works, which were designed and most of them built

in the same period as the Curutchet house, naturally eclipsed the work

studied here by their magnitude. Possibly for this reason, the historians

and researchers who have studied LC's work have rarely referred to it.

This, obviously, does not reduce its value or deny its transcendence.

In

the Curutchet House, it is not only the revolutionary concept of modern

architecture provided by him regarding the idea of a house, "La maison

est une machine à habiter," (3) that is confirmed, but also his constant

innovative aspect, his capacity for synthesis, and the outstanding lessons

provided by every work. We cannot deny that this house is a highly educational

work, with great value and interest for study and learning both at the

general level and in its position as a response to its context (its

architecture and city) (4), from its original main idea to the particular

levels of functional, formal, spatial, and technological solutions.

The singular importance of this work is found in the fact that it keeps

offering motives and answers for timely issues of architecture, and

this is possibly the most significant element of its timeless character.

Along

with the compositional analysis of this work, we will also try to touch

on another aspect which may be more profound or complex, that is, to

try to understand what the work of LC - indisputably one of the greatest

modern architects - represents for us today, at the dawn of the 21st

century, with its enormous universality and variety of ideas and its

constant offer of solutions, both in the technical and in the poetic

aspects of their development.

On

repeated occasions LC returns to the topic of the human need for beauty,

which he explains in two ways: first, as the result of the use of elementary

forms and proportional geometry, and second, as the result of a functional

appropriateness; that is, something is beautiful when it is functional.

Concerning

this house, we could say the same thing that LC stated regarding the

Acropolis of Athens: "… the apparent disorder of its design can only

deceive the profane viewer…".

The

functionality of the residence sector is provided not only by the horizontal

connections at each floor and the vertical connection of the stairs,

which we could designate as physical connections, but also by the communication

of visual order and psychological function. We should not forget that

architecture should serve to make people's life happier. In the residence,

this function of psychological service is achieved essentially through

the empty space created in the floor with the bedrooms over the living

room. An empty space that on another side, from the top floor, broadens

the perspective over the roof garden and the square. This is another

reason to recognize the functional importance of cross-sectional design.

The

idea of the journey, walk-through, or promenade architecturale that

we find in the Curutchet House had already been established by LC more

than two decades before. The fundamental objective was to offer dynamics

in the views seen during the journey, varied perspectives with unexpected

and surprising views. This consists of a search and resolution of the

topic of spatial dynamism (5) in which the value of time is managed

as one further dimension, for the understanding of human movement within

space. In this case, the ramp, as a fundamental element of the architectural

journey, exceeds the strictly functional in order to create hierarchies

within the relation of space and time.

In

the Curutchet House, the journey or promenade architecturale is enriched

significantly by the composition of architectural elements used: the

pilotis, the two-way ramp, the management of the horizontal planes of

the tiles, the volume of the residence with its recessed base, and the

tree. The entire composition serves as an answer to the dimensional

and morphological conditions of the terrain and to its location. In

addition, with these elements it creates dynamic spatial situations,

various perceptions of views and perspectives, and a consequent transition

of scale and illumination in all of its space, with the intention of

moving, in both the spatial and emotional sense, the person who experiences

the building.

The

definition of the main entrance is given by a simple element, a prism

where the door is located, which can clearly be recognized by its isolation

in the empty space of the free plan and shows us where we should enter.

It is in this prism that a strict presence and definition are assumed

by the point of change or passage from the open to the partially covered,

from light to shade, from noise to silence, from the unknown to the

answer, from mystery to revelation, and from creative exploration to

architectural drama.

The

free plan, created and used once again by LC, where the sense of its

opening is verified, allows the visual integration and incorporation

of the park within the limits of the building. In this specific case,

the free plan, defined as a threshold, was created with no other end

than to gain functional coherence and spatial significance for the entrance

along with the elements that are "freely" grouped and ordered within

the plan, and for the empty space at the center of the landplot that

is created below the residence as a complement of its width.

One

of the most outstanding elements in the spatial design of the Curutchet

house is transparency, which could be defined in this case as an inherent

quality of the organization of this building. In its design, we can

appreciate two types of transparency (6). A real - literal - transparency,

expressed as a main premise, with physical and material qualities and

direct views, that is, like a "view directly from." As its complement,

we notice a transparency that we can define as phenomenal (Greek = faínomai),

apparent as a finer and more detailed exploration and search in the

development of the design for a suggestive perception achieved by the

penetration of large masses of light through empty spaces and openings

created deliberately in order to advertise the presence of an open space

that is not seen directly, but is perceived; that is to say, in terms

of phenomena, a "perceiving through".

The

area of the roof garden, in front of the residence and above the office,

was ideally devised in terms of its location, with a view towards the

two squares in the foreground and the forest in the background. This

is a design for the enjoyment of the benefits of the sky, sun, light,

shade, and views. In the design of this building, LC exploits the shape

and position of the lot, as well as parallel conditions, in order to

achieve the best views and maximum natural light at different levels.

This forms an elaborate proposal of space management that essentially

starts from the setting (7). We could contend that the spatial result

of this house is achieved starting from a sincere and broad dialogue

of opposites which co-exist perfectly with each other, such as mathematics

and perception, reasoning (objective) and psychological experience (subjective),

geometry and plastic irregularity, restriction and freedom, unity (overall

composition) and breakdown (dematerialization and departure), full and

empty, transparent and opaque, brightness and shade, open and closed,

structural order and visual variety, rectangularity and obliqueness,

dynamism and staticity, the real and the imaginary, the expressed and

the phenomenal.

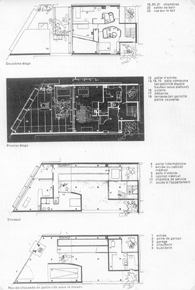

The

spatial situation of the lot, with less than 200 squares meters (8)

and with three dividing walls, where the Curutchet House is located

has as its main characteristic, as we have said before, the opening

toward two squares and the forest. Besides the consideration that for

this work, external space functions in fact like a visual magnet, since,

for any part of the house one turns in some way towards it, we can point

out three principal situations of interior-exterior relations as a direct

response to it. These appear more clearly at three different levels.

The first is at the entrance level, the second, at the office level,

and the third at the residence level.

The

most important message that we receive from this brilliant architectural

composition, starting from the spatial relationships between the inside

and the outside, is that it responds to needs of a psychological-spiritual

order, beyond the eminently material, technical, and functional.

In

the formal language of this work (residence + office), we may notice

that there is an interplay of three of the various compositional criteria

of LC's philosophy of design which we could call influences, towards

which he felt somehow attracted at the moment of designing and building.

These are pure forms in architectural volumetry, the white architecture

of the Mediterranean, and mechanistic aesthetics. With this arsenal

of forms and his favorite details, LC finds a masterful solution for

the three languages in a perfect composition through his own style of

elaboration. The dedication that LC feels as an architect is found specifically

in this elaboration, in the creation of a new language of his own, which

naturally is based on technological evolution.

In

the Curutchet House, we find various signs of the architectural language

used by LC in the majority of his works, with its respective function

and semantic value. Besides the five basic "vowels", namely the pilotis,

free plan, continuous horizontal window or fenêtre en longueur, roof

garden, and free façade, we also find curved walls, skylights in the

bathrooms, sliding doors, brise-soleils, a ramp, an open staircase,

an insulating wall, and areas with a double height.

The

rigid geometry in the façade's surface is balanced with the plastic

interpenetration of the volumes, which together achieve a varied and

changing interplay of perspectives. It consists of a functional artwork

that reflects the optimism and high ambition of one of the greatest

pioneers of the modernistic movement. We could state that in this plastic

interplay, there is a reminder on LC's part of a revision belonging

to the Purist architecture attempted during the twenties.

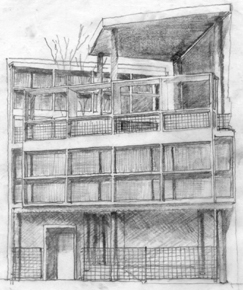

The

brise-soleil of the main façade (that of the office), which develops

from the first level above the pan-de-verre of the office and elevates

itself above the second level, that is, the roof garden, providing in

this way a frame, limits, and a scale, occupies the center of the overall

composition, both in the vertical sense, by occupying the two more central

of the four levels, and in the horizontal, by departing perceptibly

from the sides. The way in which it appears with so much empty space

beyond its four edges and behind gives us the impression that it is

suspended in the air.

The

brise-soleil of the residence, which is supported through all

its height by the constructed volume, gives us the impression of a very

perforated skin that covers the windowed front side of its "architectural

box." The heights of the brise-soleil follow the proportions studied

in the Modulor: 0.863 m for the level of the parapet and 2.260 m for

the upper level.

The

Curutchet House has an undeniable architectural value, both in the quality

of its design and implementation and because of its importance in its

historic context. Besides, the didactic virtues that it includes within

the general and specific levels of its design process offer themselves

for more extensive recognition and study.

Its

architectural value is based on the following: Firstly, a) on the contextual

manner in which it is situated as a component of the city, b) on the

resolution of zoning issues with a delicate occupation of its landplot

that considers the particularities of each one of its borders, and c)

on its elaborate central idea, design by cross-section.

Secondly,

a) on the functional resolution of the volumetrically separated and

functionally integrated themes (office and residence), b) on the spatial

richness that is developed in a singularly masterful way in such a limited

space, and c) on the volumetric response, which considers the value

of empty space as a fundamental variable to resolve the psychological

dimension of its users, within the composition of fullness that architecture

implies.

Thirdly,

a) on the formal plasticity of the complex, b) on the individual value

that it provides to the constructive and planned elements of its composition

(slabs, walls, columns, stairway, ramp, entrance prism, brise-soleils,

baldaquin, bathrooms), and c) on their articulated design, which integrates

without uniting or separates without disintegrating, which liberates

without creating anarchy and creates hierarchy without degrading.

Besides

the designed and constructed result of this work, as a product of material

resolution through technology, function, space, and form, its didactic

value can be found beyond this, that is, in the design process, where

LC enlists the incorporeal variables of psychology and perception in

his search through other paths, within and beyond architecture. The

fact that LC carried out this work at full maturity of his life and

career allows us to say that he had many more elements to measure and

involve in the design, which beyond being experimental, is a product

of experience. In this work's design process, we cannot ignore a much

wider exploration process that involves writing, observation of other

cultures, painting, sculpture, and LC's own experience from many years

of architectural practice. We find the common denominator of LC's processes

of exploration and design in their timeless character, with down-to-earth

adaptation to each circumstance, but also answers that aim upwards,

in a manner that is detached but simultaneously committed to reality,

with a high level of thought, critical thinking, and resolution. The

breadth of thought within LC's dogmatic attitude could be attributed

to his nature as an impassioned voyager or traveler and observer of

other cultures and architectural types, as a process of renewal and

subsequent transformation. In this way, LC becomes a type of apostle

to the nations, preaching the new testament of architecture, illuminated

by an Esprit Nouveau with universal and timeless principles.

Finally,

to conclude this study of the Curutchet House, we have chosen a sentence

of his which leads us to express the same thoughts that he expressed

when he began his analysis of The Lesson of Rome (9): "…all of a sudden

you touch my heart, you make me well, I feel happy, and I say 'This

is beautiful. This is Architecture. Art is here…'".

Notes

1. Norberg Schulz Christian,

Meaning in Western Architecture, London, 1975, p. 207.

2 Le Corbusier, Oeuvre Complète 1946-52, Vol. 5, Zurich 1966.y Œuvre complète

1952-1957, Vol. 6, Zurich 1968.

3 Le Corbusier,

Vers une Architecture, Paris, 1958, p. 83.

4 Arrese Alvaro, "Le Corbusier y La Plata", Summa 181, Buenos Aires 1982,

pp. 38-39.

5 Tomas Héctor, El lenguaje de la arquitectura moderna, La Plata, 1997,

pp. 159, 177-179.

6 Rowe Colin, Manierismo y arquitectura moderna y otros ensayos, Barcelona

1982, pp. 155-177.

7 Pérez Oyarzún Fernando, Le Corbusier y Sudamérica, viajes y proyectos,

Santiago de Chile, 1995, pág. 143. Liernur Francisco - Pschepiurca Pablo,

"Precisiones sobre los proyectos de Le Corbusier en la Argentina 1929/1949",

pág. 40-55, Summa 243, Buenos Aires (11/1987), pág. 52.

8 The approximate dimensions of the lot are the following: 8.90m perpendicular

width, 23.05m long side, 17.40m short side, 10.30m diagonal façade.

9 Le Corbusier, Vers une architecture, "… Mais tout à coup, vous me prenez

au coeur, vous me faites du bien, je suis heureux, je dis: c'est beau.

Voilà l' architecture. L' art est ici…", pág. 123.

Claudio

Daniel Conenna